Intercepted: Gender (In)Equity On and Off the Field

When you google the word “intercepted” this is what you find:

verb

past tense: intercepted; past participle: intercepted

/ˌin(t)ərˈsept/

obstruct (someone or something) so as to prevent them from continuing to a destination.

"intelligence agencies intercepted a series of telephone calls"

synonyms: stop, head off, cut off; catch, seize, grab, snatch; obstruct, impede, interrupt, block, check, detain; ambush, challenge, waylay"the ball was intercepted"

It’s normal—and even encouraged—to intercept passes from the other team. This can help you win a game. But what happens when you intercept passes within your own team? Who wins then?

This is a story about flag football, gender socialization, and how it all shakes out in the workplace.

Setting the Stage: A Guys’ Hang-out?

That was the message one of my classmates posted to our cohort’s Facebook page. After spending 9 years living in Shanghai, China, I was in the “repatriation” process into a city that I had never lived in—or even visited. I knew very few people outside of those in my classes, and being a decently extreme extrovert, I was eager for opportunities to connect with more people. And, of course I would never pass up on the opportunity to do something active—I loved sports and the outdoors.

However, the probable reality of the situation swirled in the back of my mind: My male classmate’s male friend was getting people together to play flag football. All signs pointed in the direction that this was a “guys’ hangout ” to which the presence of a woman would not be welcomed. I was assured by my friend this was not the case: “Of course you can come! It’s open to anybody!” I didn’t quite believe him, but I was hopeful his statement that anyone was welcome would prove to be true.

The Problem of Gender-Socialization Soup

To be clear, my hesitancy to play had nothing to do with the fact that I might be the only woman in attendance. My hesitancy instead had everything to do with the environment into which I might be stepping if I was the only woman at an event billed as a “guys’ hang out”. These were often environments that explicitly or implicitly communicate “you don’t belong”. Environments many women both on the field and in the workplace are all too familiar with. I believe that it is this environment—not that women are for some reason less willing or able to play sports or do STEM—that fuels the lack of representation on the fields as well as in some workplaces. Let me explain.

Boys and girls are socialized from a young age as to what is appropriate for their gender—both what they should like and how they should act. Throughout life, boys, girls, men and women are either rewarded for living into their gender role, or punished for going outside of it. By the time we are adults, we look at the sports field, STEM workplaces, nursing field, education, etc and, seeing a noticeable imbalance between the representation of men and women, we conclude that this imbalance is because of a person’s gender. Boys, girls, men, and women must just innately like and be good at some things more than others. This “soup” that we’re all socialized in creates mental-models, stereotypes, and biases that we then reinforce through who we invite to certain functions, who we hire for certain positions, and who we see as the “best fit” for a role (be it professional, political, or personal).

This environment of the flag football game was likely to be an environment which would not by default embrace me. Women in tech, or women who like to game, too often have a similar experience. These women must courageously opt into an environment that will do much to exclude them, simply to be a part of something they love. This day, I too chose to put sport above the possibility of exclusion.

For the Love of the Game

Myself, my friend who had made the invite, and another male classmate arrived late to the field. As we walked toward the game, already in play, I visually scanned the field. Nine men. No other women. My heart sank. I had indeed “crashed” what was clearly a “guys’ hangout”. My mind flitted quickly through other potential activities: going for a long run instead...watching...my mind went blank and it was too late anyway. They had seen me, I had my cleats, I was obviously there to play flag football, not to ride with my friends and do a run or watch. Additionally, my competitive streak and my desire to prove that yes, women can play sports, kicked in: there was no way they were going to think that I wasn’t playing because I couldn’t and there was no way I was going to perpetuate a stereotype of women just because I was a little uncomfortable.

Plus, they needed me for the teams to be even.

We all gathered in a group and randomly put our hands face up or face down in the center of the circle to break up into teams. My two classmates ended up on one team. I was on the other. Great. The few guys in the group who actually knew I was competent at sports and would be potential allies in the upcoming game were now on the opposing team.

I’m athletic, and know that I can not only keep up with, but even potentially outplay, many guys (as can many other women). As the classic rebuttal goes, they don’t have to worry about me “bringing down the level of play”—a statement which is akin to a hiring manager asking if they should hire the most qualified person, or the person of color. The words we use say a lot about the assumptions, stereotypes, and biases we carry. These particular statements reflect how the default assumption is that on the sports-field any man will outplay any woman, and within hiring, is that the white person is always more qualified than the person of color.

What a Flag Football Game Has to do With the World of Work

We began playing, and in this one small game I experienced a sample of the gender and power dynamics many women and people of color face in their everyday life and work.

Potential vs Ability

Since I had never met—let alone played a sport—with anyone on my team before, I knew that I was going to have to play exceptionally well to convince them that I could be trusted to catch a pass, guard an opponent, or outrun a defender. As we started to play I felt the pressure to perform perfectly, to not drop a single pass—and especially not the first pass as this might ruin any chance of future receptions.

As with sports, in the workplace, many women and people of color have the same experience: their abilities are not assumed, they have to be proven. And proven again. And proven again. White men, on the other hand, more often have the subtle advantage that people assume their abilities until proven otherwise. Research on hiring and promotions shows that more often, men are evaluated on their potential, while women are evaluated on their proven ability [1] [2].

Prove it Again Bias

In a soccer game if a guy tries to dribble through four people and loses the ball halfway, those watching often focus on how amazing his ball handling skills were through those first two players. On the other hand, if a woman tries the same thing, what is often focused on is the fact that she lost the ball, or didn’t pass when she could have. It is too often assumed that the guy could have dribbled through all four players, and it just didn’t work out this time, while for the woman this same event would infer that she doesn’t have the ball handling skills to dribble through that many players. Even if she is successful, her skill isn’t necessarily proven—maybe she just got lucky. In social psychology this is called “prove it again” bias. Within my game of flag football, I knew that I would need to prove myself...and prove myself...and prove myself.

The Scripts We Live By

While we are all socialized in the same soup to believe that some things are “for” women and some things are “for” men, bias operates differently—and to various extents—across people. In this personal and thoughtful TEDTalk, actor Justin Baldoni (who you might recognize from Jane the Virgin) talks about the gendered scripts we all grow up with, and shares his attempt to redefine masculinity. Within the flag football game, it was interesting to note how these types of scripts and biases caused various men on my team to interact with me.

In general these scripts could be generalized into three categories: The Protector, The Ignorer, The Ally. Each of these characters played a different role in my feeling either included or excluded from the flag football game. Each are characters I have come across not only in this flag football game, but in other sports, in social environments, in the workplace and in stories shared by other women. In reality, each of us is a mixture of these characters—living out to various degrees the scripts of Protector, Ignorer, and Ally. By putting these scripts into three distinct characters my hope is that each of us will be able to better reflect on the things that we should keep doing as well as the things we should stop doing in the quest to create an inclusive environment for all. I will outline each character next.

The Protector

“How are you doing?” One of my teammates asked with a slightly concerned tone about half-way through the game. I was a little thrown off by the question. It seemed to imply that something about how I looked or how I was acting would indicate I was not doing okay. However, as far as I could tell I was doing fine. “I think I’m good” I replied laughing a little, then continuing, “why?”.

“Oh, no reason. Just thought I’d check in.”

It’s not that this is a terrible question. But it’s also a question that he didn’t ask of anyone else on the team. Underlying this question (and the fact that he did not ask it of anyone else on the team) is the conscious or subconscious thought that because I’m a woman I might not be doing okay. He was really just trying to be nice, and I knew that. The intent was good, but he didn’t take into account the context of the question (did he feel the need to ask others on the team the same question?) or it’s possible impact (when I was the only person asked and the only woman present). For me, the impact was a subtle reminder that I’m the only woman in the group and that the assumption (generally speaking) is, as a woman, I might be struggling to “keep up with the guys”.

The Protector approaches this situation not from a desire to keep women out—but with the desire to “protect” them in a space where women aren’t the majority. To make sure that they don’t get “hurt”. The thing is, we don’t need or want protecting—we want partnership and to be treated like an equal part of the team, just like anyone else. As on any good sports team, within the workplace people want to know that their co-workers are looking out for them, trust them, see them as capable, and are ready to offer a hand if needed. In the workplace The Protector may be the person who questions suggesting that a woman be considered for a promotion because they know she has kids at home and isn’t sure she’ll want the increased amount of travel that comes with the new position. If you ask The Protector directly whether or not they think a woman can do the job they’d likely say “of course!”. A report by Catalyst showed that a statistically significant greater number of men had the opportunity to work on global teams (88% of men, 77% of women) and to relocate internationally (28% of men, 17% of women) than women. This is an important gap, as international experience has been shown to be a key factor contributing to advancement within a company. Don’t assume anything about a person’s situation and how that might affect what they want to be involved in or don’t want to be involved in—simply ask them.

How ‘The Soup’ Informs Action

Give women the same opportunity to make decisions about their involvement in the workplace that men have. Give men the same option to focus on family that is too often assumed only something women “should” do. Let’s find a balance. As Sheryl Sandberg says, we all need to lean in together.

Yes, it can be a fine line between simply being nice or thoughtful and becoming The Protector. One thing to ask yourself is: would I ask this same question or make the same assumption of people like me? Do you hesitate to offer a promotion that requires more travel to the men on your team who have young children at home? In my flag football game, this teammate was not asking all the other people on our team how they were doing, he was only asking the woman on his team how she was doing—and therein lies the rub.

Another question to consider is: How will this question land with or impact this particular person or group? A good example here is the question: “Where are you from?”. Ken Tanaka’s viral YouTube video has a comedic but painfully true example of this. The experience of many people of color is that the underlying assumption of the questioner is that they are not from the US. This is displayed through the follow-up question they too often receive: “No, where are you really from?”. If I truly care about other people, and have taken the time to better understand their particular experience, I’m going to allow that knowledge of their experience, and the felt impact of certain questions, to influence the way I interact with them, get to know them better, and support them. I’m going to realize that even though my intent is good (getting to know a person), the impact may be bad (making them feel like an outsider) and that these two things should inform how I act on my intent. It’s the practice of building empathy.

So what could this guy on my flag football team have said?

“Wow, I’m getting so tired, haven’t run this much in a while.”

Or he could have been direct: “Your face looks a bit purple, are you okay?” To which I would have been able to laugh and assure him that the color of my face was a blessing disposed on me at birth because of my red hair, fair skin, and the fact that my capillaries are either closer to the surface of this fair skin or dilate more than average (or both), thereby making my face turn red way too quickly upon exercising. I would have been able to assure him that it was merely the luck of genetics, and not an indication of my impending doom. But he did not ask this, he asked me, and only me, “are you okay?”.

The Ignorer

This one is pretty straight forward. The ignorer operates as if the other person doesn’t exist. In the flag football game there were a number of guys that never really acknowledged me as a part of their team. They weren’t necessarily mean—they didn’t tell me that this wasn’t “for” women or tell me to leave—but, as far as they were concerned I didn’t exist. They didn’t yell at me if I missed a pass. They didn’t give me a high five if I caught a pass. They did run in the exact route I had been told to take by the quarterback. They did cut me off as I was making a run (and out-running my defender) to catch a pass. They didn’t see me, nor did they try to.

The Ignorer in the Workplace and Life

The Ignorer is the person who shares an idea, only moments after a woman has shared the same idea, and doesn’t even notice. The Ignorer is all the people sitting around the conference table who act like the idea was indeed shared for the first time. The Ignorer is the person who “absentmindedly” cuts a black person off in line, then says “Oh! I’m so sorry, I didn’t see you!”. In a gendered and racialized society, the Ignorer has been socialized to not “see” certain people. And the not seeing is oddly correlated with race or gender or dis/ability.

The real bummer is that as a woman, I too can pass to the men on my soccer team instead of the women because I have been socialized in the same soup. I have grown up (for the most part) with the same narratives and scripts about what women are “best” at and what men are “best” at. Being a woman doesn’t make me immune to acting on these scripts that have been deeply imbued on my way of being. In meetings, women get interrupted more than men. The Podcast More Perfect has a fascinating episode that dives into this “epidemic of interruptions” in the Supreme Court. The default thought is that if women are getting interrupted it’s men who are doing the interrupting.

However, in practice, all genders interrupt women more than they interrupt men. So bias and not “seeing” is not only a male problem or a white problem or a heterosexual problem—it’s a human problem. At the same time, there is a lot to be said for the power of the lived experience. It’s hard to know what you don’t know (and being able to recognize this is a powerful thing). For this reason, those of us from dominant, in-power groups are less likely to notice when we are not “seeing” something. We have to be intentional in our learning.

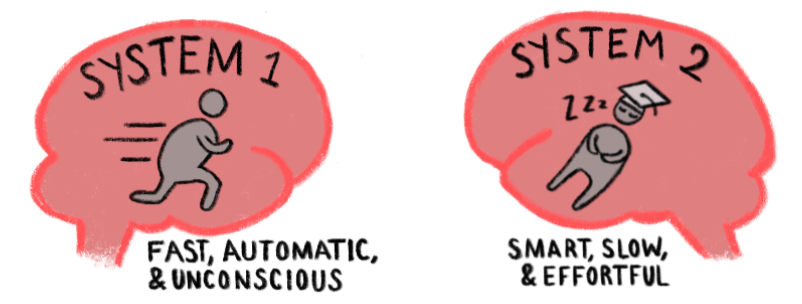

System 1 & System 2 Thinking

Awareness and acknowledgment of our own tendency towards bias and not “seeing” is the first step in offsetting socialization. In the book Thinking, Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman brilliantly explains the way our brains operate through the use of two systems: System 1 and System 2. System 1 is automatic, involuntary and often operates with little effort—helping us process the many unconscious decisions we make every day without being overwhelmed. System 2, in contrast, requires deliberate thinking and energy—and thus can be quite lazy. To change any of our automatic behaviors that have become programmed into System 1, we need the intentional help of System 2.

Because I am aware that I am socialized to generally favor men over women when it comes to athletics, or to interrupt women more often than men, I can then take conscious steps to counteract these tendencies. I have to actively engage in changing the narrative and scripts that have shaped me, not simply passively believe that because I want to treat all genders equally that it will automatically happen.

The Paradox of Meritocracy

In fact, believing that we treat people equally and not intentionally being conscious about our actions has the potential to actually make some actions more biased. Crazy right? In a study Emilio Castilla and Stephen Benard found “when an organizational culture promotes meritocracy (compared with when it does not), managers in that organization may ironically show greater bias in favor of men over equally performing women in translating employee performance evaluations into rewards and other key career outcomes”. They call this the “paradox of meritocracy”. Recently, the company SalesForce realized that it had a gender pay gap. At first CEO Marc Benioff was incredulous. His experience was that SalesForce had a great company culture, had received awards as one of the best places to work, and he believed that paying people differently based on a dimension of difference was simply something that didn’t happen there. Until he saw the data. Benioff and his team then had to be intentional about not only closing the pay gap, but also about putting systems and processes in place to make sure the gap stayed closed. They started with awareness, and then took intentional steps towards putting systems and processes in place to support their desire to treat people equally—they knew that just wanting to treat people equally wasn’t going to be enough.

The Ally

The Ally actively engages System 2 thinking, believes the stories of those in non-dominant groups, intentionally behaves towards those who are different from them with reciprocity, and humbly acknowledges that they won’t always get it right.

The Power of Allies

Looking back on this flag football experience, I had one ally on my side of the field—luckily, this ally was also the quarterback and he held a unique position of power within the realm of football. He noticed that I could (often) outrun my opponent and that I could catch a football—and he gave me opportunities to do so. When another teammate took the running path he had assigned to me, he called this person out for cutting me off. Feeling supported, trusted, and having my skills as an athlete recognized helped me to feel less pressure to perform perfectly or to need to prove myself again and again. This freedom likely increased the level of my own playing as, being less fearful of the possibility of opportunities being limited as a consequence of failure, I was willing to try things even if I might not succeed.

The same scenarios play out in the workplace. Allies leverage their power alongside—and for the benefit of—those with less power. French and Raven outline six types of power that a person can have including: being in a certain position (management, leadership), the surrounding society or culture and the norms this society/culture has, the value this culture gives certain groups (being able-bodied, male, cisgender, heterosexual, white), through holding information (education, expertise), having the ability to give rewards, or simply being in the spotlight (professional athletes, actors).

The ally from flag football has since become a close friend. We’ve laughed many times while retelling the story about the first time we met when, in his words: “My friend brought some woman to a guy’s hang out and then she totally killed it”. We’ve also had candid discussions about the stereotypes associated with women in athletics, his own default assumptions that he has had to challenge, and how this relates to the work we both do within the field of diversity and inclusion in the workplace.

Intentionally Pause and Engage System 2

Ironically, this ally’s first response when I showed up to the field was not to be inclusive, it was more of a: “Great...my friend brought a girl.” And this “great” wasn’t the: “Great, ice cream!” great. But instead the “Great, the dog peed on the floor again”, great. However, even after this thought, he took a key step: he paused and intentionally engaged System 2 thinking, recognized the bias operating unconsciously in System 1, and decided that it didn’t matter, he was going to welcome me and make me feel included no matter his initial hesitation.

It always takes intentional work to be an ally—to recognize where System 1 thinking renders someone invisible, causes us to not “see” them for all they are, or causes us to make assumptions about what a person can or can’t do.

The Imperfection of Allies

Most of all, being an ally doesn’t mean that we’re immune to making mistakes. Socialization starts early and the behaviors it embeds run deep. This doesn’t mean that we don’t have a responsibility to be intentional about changing these scripts and providing better, more accurate, ones for future generations, but it does mean that sometimes (often in times of hurry or stress) we will fall back on our more ingrained System 1 behaviors and narratives. When we do this, or when the consequence causes someone else pain, an ally is responsible for humbly seeking reconciliation—starting with a recognition of their own contribution and behaviors in this wrong. Since this could be an entire other post, I’ll instead direct you to two articles I feel give good ideas in this area. One provides 9 phrases allies can use when they make these mistakes and are called out, rather than getting defensive. The other looks more broadly at how we should respond when an ally becomes a perpetrator within the exact sphere they are supposed to be an advocate. Each article contributes valuable tips and reflections for those seeking to do their own learning in how to be a better ally to those around them.

At Greatheart Consulting, we frame the trajectory of progress towards being an Inclusive Leader within 5 Stages: Pre-Awareness, Interest & Necessity, Careful Skill Progress, Adventurous Competence, and Relative Expertise. Within these stages we emphasize intentional engagement, that progress requires challenging ourselves and stepping into new environments where we might make mistakes, and that the process of becoming a person who leads inclusively is one that is ever-continuing. We may find ourselves in a different stage depending on the dimension of difference in question. In some areas we may exercise Relative Expertise due to our lived experience or intentional learning, while in others we will flounder and make mistakes as we practice careful skill progress. The important thing for each of us is that we work to become more aware each day of how people who are different from us experience the world, and that we seek to be allies to those around us, using the type(s) of power we hold to increase universal liberties for all to live as their authentic selves.

Illustrations by Cyrena Johnson